Written by: Mihai Oancea

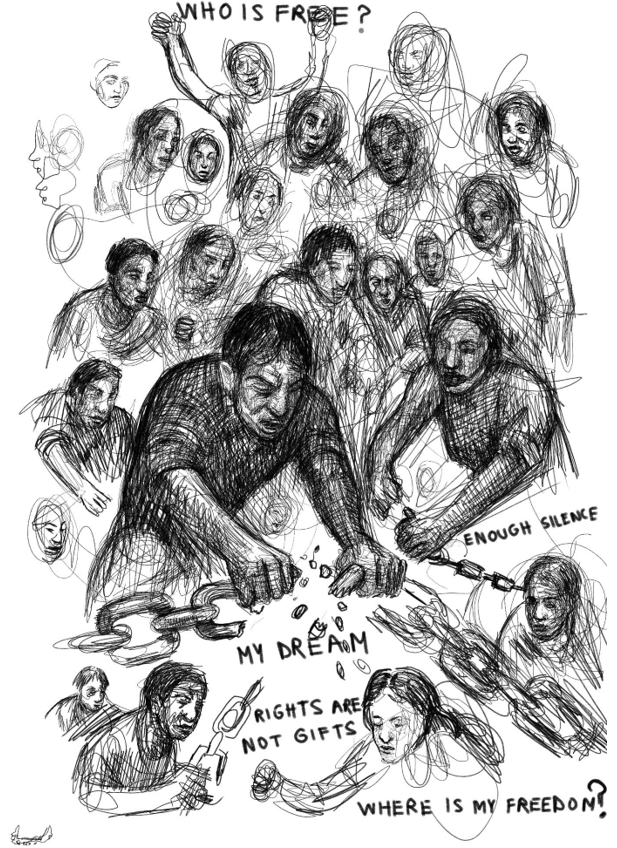

Emanuel Barica, 2025,, Broken chains. Raised voices. One question: Who is free?’’ from the exhibition ,,Ame Sam Terne – We Are Young’’ ternYpe International Roma Youth Network

In February 1856, slavery was abolished in Wallachia. One year earlier, in 1855, it had already been abolished in Moldavia. After almost five centuries, Roma were no longer legally owned by the state, monasteries or private landowners.

One hundred and seventy years later, this history still feels unfinished.

When we speak about Roma slavery, we are not speaking about a distant injustice locked in archives. We are speaking about a system that shaped generations. It shaped where people lived, what they were allowed to own, whether they could move freely, whether their children were theirs to keep.

For centuries, Roma were treated as property in the Romanian Principalities. In the seventeenth century, official charters confirmed the ownership of Roma men together with their children, listed in the same legal formula used for land or other goods. By the early eighteenth century, rulers were issuing orders to track down Roma who had fled monasteries and to return them, together with their entire families, regardless of their will. The language of these acts is procedural and controlled. Slavery functioned through seals, signatures and instructions, embedded in the legal order of the time.

(Archival documents from 1634 and 1715, reproduced in Adrian-Nicolae Furtună & Victor-Claudiu Turcitu, Roma Slavery and the Places of Memory, 2021, National Archives of Romania.)

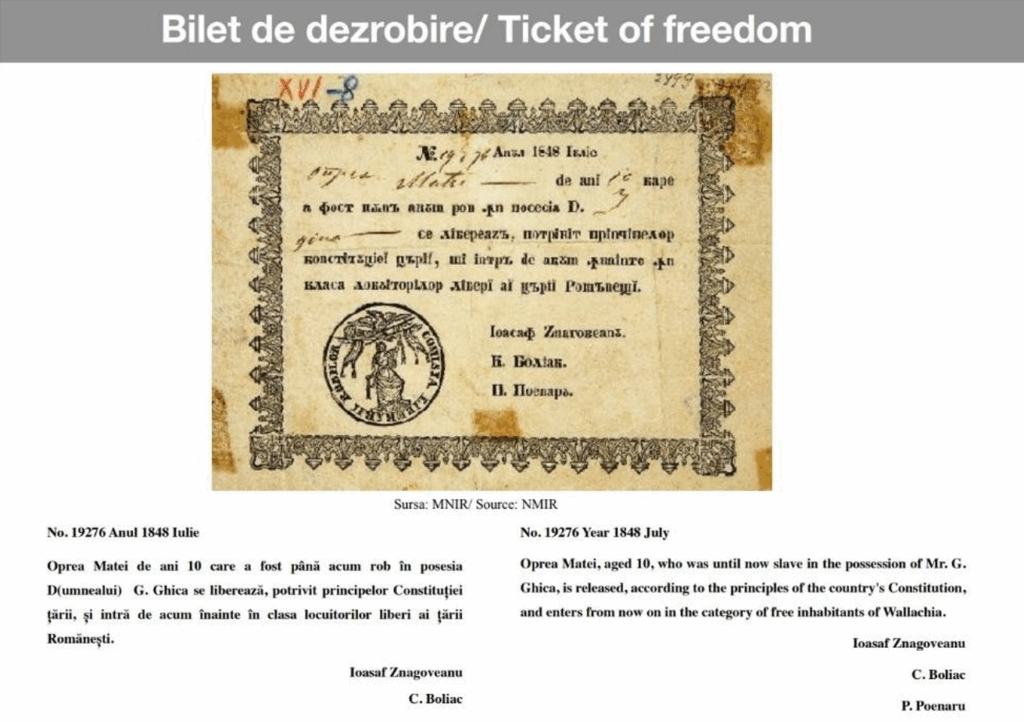

The path toward abolition was equally bureaucratic. In July 1848, a ten-year-old boy named Oprea Matei was officially released from slavery. A document records that he would “enter the class of free inhabitants” of the country. A child who, the day before, had been legally owned, became free through a stamped certificate.

(Ticket of freedom, 1848, reproduced in Furtună & Turcitu, 2021.)

In 1856, in Iași, a theatre play celebrated emancipation. The foreword described abolition as an act of generosity and a sign that the country was worthy of civilized Europe. The audience applauded. The country moved forward.

But freedom on paper does not immediately undo centuries of exclusion. There was no land reform for former slaves. No serious long term plan for integration. No collective acknowledgement of harm. A legal status changed, but social hierarchies did not disappear overnight.

For decades, Roma slavery remained almost absent from public education. Many Roma grew up without learning the full weight of what their ancestors endured. Many non Roma grew up without ever being told that slavery had existed here for nearly 500 years.

Marking 170 years should mean more than repeating a historical fact. It should make us pause and ask what this history still shapes today.

For those of us who belong to the younger generation, this is a moment of clarity. The inequalities we see around us did not appear from nowhere. They are linked to a long history in which Roma were denied property, mobility, education and voice. Understanding that does not trap us in victimhood. It gives context to what we continue to challenge today.

Our communities endured five centuries of enslavement. They endured deportations during the Second World War. They endured forced assimilation and daily discrimination. Yet they also built families, traditions, music, language, and ways of surviving with dignity even when dignity was denied. That quiet strength runs through generations.

One hundred and seventy years after abolition, the meaning of freedom must be deeper than a historical date. It must be visible in classrooms where Roma children are not segregated. In institutions where Roma youth are not tokens but decision makers. In public spaces where identity does not invite suspicion.

If we do not speak about it, it disappears again. And when it disappears, so does the chance to understand why certain inequalities persist. A society that knows its full story has a better chance of becoming fair.

In 1856, a law declared Roma free.

In 2026, the question is simple and uncomfortable: are we living up to that promise? The answer will depend on what we choose to build from here.